Dans le ciel

Edition first assembled and edited by Pierre Michel in 1989 | |

| Author | Octave Mirbeau |

|---|---|

| Original title | Dans le ciel |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | L'Échoppe, Caen |

Publication date | 1892 |

| Publication place | France |

Dans le ciel (In the Sky) is a novel written by the French journalist, novelist and playwright Octave Mirbeau. First published in serialized installments in L'Écho de Paris between September 1892 and May 1893, Dans le ciel, assembled and edited by Pierre Michel and Jean-François Nivet, first appeared its present form in 1989.

English translation : In the Sky, Nine-Banded Books, Charleston, 2015. Translation : Ann Sterzinger. Introduction : Claire Nettleton.[1]

Plot summary

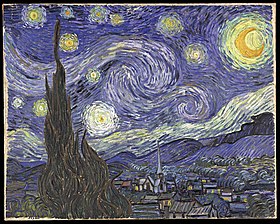

[edit]Inspired by the art of the Impressionists – using Claude Monet and, mainly, Vincent van Gogh as models for its central characters –, Dans le ciel conveys the author's growing conviction that the only worthwhile art communicated its striving for the incommunicable and that the finished work could express no more than the frustration of its goals.

A series of interlocking narratives, the novel begins by relating the creative failures of the self-styled novelist Georges, who produces nothing but an unfinished autobiography, then chronicles the poignant struggles of the painter Lucien, whose inability to complete his masterpiece culminates with his suicide when he severs his own hand. It is with the discovery of the terrible fate of the self-mutilating artist that Mirbeau's truncated narrative is itself left in suspension.

Commentary

[edit]In the novel's disjointed, fragmentary structure, Mirbeau expresses his rejection of the artificial unity of conventional novelistic form. As referred to in the title, it is in the sky that the artist locates the uncapturable ideal and on the terrestrial plane that the story of his creative tragedy plays out. Octave Mirbeau’s text focuses on the unbridgeable distance between the inspiration orienting the artist upward and the heavy, gravity-bound smallness of his limited ability.

Since the artist can never express with the « clumsy, faithless tools of his head and hands » [2](Michel and Nivet), the perfect beauty he intuits, his art becomes an experience of suffering. The existential struggle of the artist, like Lucien, whose labor is foreordained to come to nothing, suggests that the creator maintains his dignity through a refusal to surrender and that he attains nobility in the rejection of compromise and the determination to persevere.

Characters

[edit]Lucien

[edit]Lucien is one of the central fictional characters in the novel. He is the friend of the embedded narrator, Georges, to whom he has bequeathed his house, situated on a fantastic mountain peak that rises vertiginously into the sky. Lucien is modeled on Vincent van Gogh, whose paintings The Irises and The Sunflowers Mirbeau himself had purchased, and whose masterpiece The Starry Night is attributed to Lucien. However, while considering the Dutch artist to be entirely sane, Mirbeau portrays Lucien as becoming gradually unhinged. Still, Lucien is meant to be taken as an entirely imaginary character, in no way a faithful rendering of his real-life counterpart. Like Clara in Le Jardin des supplices (The Torture Garden) and Célestine in Le Journal d’une femme de chambre (The Diary of a Chambermaid), Lucien is given no last name. The son of a butcher, Lucien had had the good fortune to emerge « sound in mind and body from the stupefying regimen of secondary school », and thereafter, against the wishes of his father, had elected to become a painter – in the same way that l’Abbé Jules, from the novel of the same name, had chosen to become a priest, « By God! » Lucien’s artistic credo can be reduced to the formula he never tires of repeating: « See, feel, understand. » But Lucien’s conception of art remains confused, as he moves back and forth between Impressionism, Divisionism, and Expressionism. Never able to express his ideal of art in words, he aims too high, and the works he completes are always tragically inferior to those that he imagines, the works that his refractory hand is incapable of executing : « The deeper that I penetrate into the inexpressible and supernatural mystery of nature, the weaker and more impotent I feel in the face of such beauty. Perhaps one can conceive of nature vaguely in one's mind, but rendering that conception by using the crude, awkward, and untrustworthy instrument of the hand – that, I believe, is beyond one's human capabilities. » Thus, in the course of his development as a character – having forgotten his original convictions and lost himself in the aesthetic of the Symbolists and Pre-Raphaelites, whom Octave Mirbeau had earlier skewered in his Combats esthétiques – Lucien ends by committing suicide after cutting off his “guilty” hand. In creating a character who constantly challenges himself, who constantly aspires to an absolute that is impossible and unattainable, Mirbeau explores the tragedy of an artist who is uncompromising, unwilling to conform to the academic traditions of art, and who, rather than submitting to them, confronts head-on the institutionalized prejudices encountered in the world of politics, the fine arts, and a public inhospitable to change.

References

[edit]- ^ In the Sky, Nine-Banded Books, 2015.

- ^ Pierre Michel and Jean-François Nivet, Octave Mirbeau, l'imprécateur au cœur fidèle, Librairie Séguier, 1990, p. 478.

External links

[edit]- (in French) Octave Mirbeau, Dans le ciel[permanent dead link], Éditions du Boucher, 2003.

- (in French) Pierre Michel, Foreword.

- (in French) Robert Ziegler, « Vers une esthétique du silence dans Dans le ciel », Cahiers Octave Mirbeau, n° 5, 1998, p. 58-69.

- (in English) Robert Ziegler, « The art of verbalizing the barking of a dog : Mirbeau's Dans le ciel », 2005.

- (in English) Claire Nettleton,« The Animal and Aesthetic Nihilism in Octave Mirbeau's Dans le ciel »[permanent dead link], in Primal Perception: The Artist as Animal in Nineteenth-Century France, Los Angeles, 2010.